By Steph Acosta in collaboration with Brendan Ryan

Five years ago, I opened the door to my sister’s house. Before I could say hello, my nephew Alex, who was 7 at the time, grabbed my hand. “Let’s go,” he said, pulling me right back through the door.

“Where are we going?” I asked. “The swings,” he said, with a broad smile lighting up his face.

On the walk there, he told me all about the swings and why he thinks they are great. “You go up and down,” he said. “They move fast. You feel so free on them. The harder you pull, Aunty Steph, the more you push up; the higher you go. It’s so cool.”

After about a minute of swinging, Alex had finished and moved on: first, the slides, then the monkey bars, followed by the rope climb, jungle gym and general socializing with other little people ― he tried everything. As much as he was having a blast, I was annoyed. I hadn’t seen my sister in a long time and had delayed my visit so he could feed his slide habit. General playground euphoria was not what I had agreed to provide. However, as Alex played, I realized something: As much as he liked the swings, what he really loved was learning new things, and that’s a very good thing. That thought made me really happy too.

Alex was successful at some of the things he tried, such as the monkey bars. On them, he made it all the way across. But on other activities, he wasn’t so successful ― he fell off the rope climb every single time, for instance. Interestingly, to Alex, there was no success or failure; the results were completely unimportant. His focus was on learning new skills for the sake of the learning.

Alex eventually got tired of playing, and I got to catch up with my sister. Afterwards, as I was driving home, I resolved to make the lessons I teach look more like Alex’s playground session: “Learn; no success or failure; have fun and want more” ― Alex’s goals at the playground became the “True North” of the lessons I teach.

Recently, Alex, who lives in a country far from me, joined me at the golf course for a lesson. He’s 12 now, an athletic kid who has a passion for golf. When he arrived, I gave him some simple instructions, “Hit some shots, and each time you do, pick a different club and target.” As he hit his shots, I conducted my evaluation. I came to the conclusion that Alex lacked an understanding of separation in the back swing, which was in part due to an unstable base. Without explaining anything, I asked him, “Do want to play a computer game?”

“Yes,” he said, smiling widely. “What’s the game called?”

“‘Ding,’” I told him. “You make the computer ding.”

“That’s it?” he asked.

“That’s it,” I told him. “What we are going to do is put on this vest and belt, and then an avatar will appear on the computer screen along with some arrows. You follow the arrows to move the avatar and get a ding. That’s the game.”

“Cool,” he said, nodding his head, still the bold discoverer of new things, on-board with the project, but a bit underwhelmed.

In less than a minute, he was playing his new, custom-built-for-him computer game. What was this “game”? A K-VEST NEXT program, set to combine the drill advanced posture with the 20–40 takeaway drill and the side bend at the top drill. This program let him “discover” — completely on his own — the movements I wanted him to learn.

At first, Alex struggled, but he understood what he needed to learn to do to make the ding sound. The more he struggled, the more into it he got. I didn’t have to say a word. He used trial and error to learn by making experiments that got him the dinging sounds. This continued for about 10 minutes: some dings and some struggles. And then it was “ding, ding, ding.” He was completely absorbed, loving it, as well hitting beautiful shots. One after another, each shot accompanied by, “ding, ding, ding.”

“This is awesome,” he told me. “Ding is a great game, and it’s good for my golf, too.”

That long-ago experience in the playground really was a turning point for me as an instructor. I no longer use what I now know is called a “closed feedback loop”: Student does something; student gets feedback of success or failure from me the instructor, and then does it again.

What Alex was doing, I came to learn, was using an “open feedback loop”: Student does something with feedback embedded into the activity and never stops doing or learning — with no feedback from the instructor.

Today, with my K-VEST biofeedback, I provide this kind of learning situation to all my students. And to them, just like Alex, it’s a game called “Ding.”

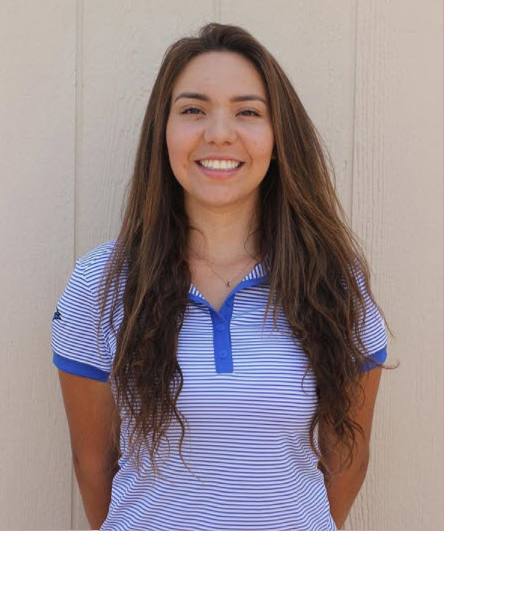

Steph Acosta

Estefania Acosta-Aguirre is a former college coach and player who has won an individual conference championship and two PGA Minority National Championship. She holds an undergraduate degree in Psychology with a minor in International Business, and is a K-Vest, Flight Scope and Putting Zone Certified Coach. She is currently pursuing her masters in Sports Coaching at the University of Central Lancashire, as well as finalizing her second book due out in early 2018. You can follow her on Instagram at steph_acostacoaching

Estefania Acosta-Aguirre is a former college coach and player who has won an individual conference championship and two PGA Minority National Championship. She holds an undergraduate degree in Psychology with a minor in International Business, and is a K-Vest, Flight Scope and Putting Zone Certified Coach. She is currently pursuing her masters in Sports Coaching at the University of Central Lancashire, as well as finalizing her second book due out in early 2018. You can follow her on Instagram at steph_acostacoaching

Brendan Ryan

Brendan Ryan is a golf researcher, writer, coach and entrepreneur. Golf has given him so much in his life — a career, amazing travels, great experiences and an eclectic group of friends

Brendan Ryan is a golf researcher, writer, coach and entrepreneur. Golf has given him so much in his life — a career, amazing travels, great experiences and an eclectic group of friends

The MLB Winter Meetings brings together baseball executives, coaches, media, exhibitors and job seekers from around the world to network, fill job openings, attend educational workshops and discuss innovating trends in the industry. It’s one of the highlights of our…

Agreement to Accelerate Improvement Across All Levels of the Organization (SCOTTSDALE, Ariz.) K-MOTION – the leader in 3D evaluations and biofeedback training solutions for coaches and athletes – announces an agreement with the Baltimore Orioles to become the organization’s Player…

By Joe DiChiara and Jason Meisch You take a swing and don’t like where the golf ball goes. You want to know what happened, so you turn to your launch monitor. You look at the club face numbers. They tell…